To keep up with traditions, I post today on my blog to celebrate my 14 years journey to Batik. Normally I share a Batik Statement in the form of a photo or photoseries. I did of course share photos on social media for this celebration. But for here I though I share a writing I did last Summer, that until today didn't get published. So might as well share it here. A Batik Statement in essay form, a first!

I would like to thank everyone who joined me, supported me & guided me on this journey to Batik. I hope I can learn, study and enjoy Batik for many more years to come. I would like to thank the pembatiks, those of the past and present for keeping this amazing legacy alive, terima kasih banyak/Matur nuwun!

Selamat membaca, have a wonderful Hari Kartini! Selamat Idul fitri and thank you for visiting my blog today!

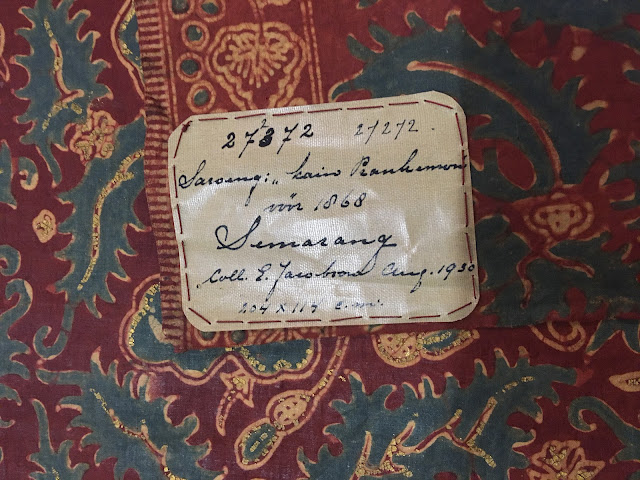

Label on batik that was attributed to Von Franquemont

WM-27272, collection Wereldmuseum Rotterdam

Re-telling the history of the (Indo-)European influence on Batik - Sabine Bolk

In my research project ‘Re-telling the history of the (Indo-)European (2) influence on Batik’, the goal is to re-tell the history of (Indo-)European influence on Batik between 1850 and 1890. I chose this timeframe, because according to literature (1) this is when a European influence became visible in Batik designs. In my research I work with re-telling in words and images to give answers to the following question: How was Batik influenced by Europe?

Von Franquemont as a starting point

My research starting point is Carolina Josephina von Franquemont (1817-1867).

Von Franquemont is a well-known name within the Batik community. In literature (1) it is written that she was the first Indo-European to run a Batik workshop around 1850 on Java, Indonesia. That she was locally known under the name ‘Prankemon’ and famous for her use of a green dye.

Several Batiks from collections worldwide are attributed to Von Franquemont, attributed as in thought to be made by her or made in her Batik workshop. Von Franquemont did not sign her Batiks and almost all attributions were made decades after her death in 1867.

To re-tell the history of the (Indo-)European influence on Batik, I use the story about, and Batiks attributed to Carolina Josephina von Franquemont as a starting point. I started mapping out what is actually the Dutch, European and Indo-European influence on Javanese Batik. How is it described in literature1, what sources are there, who wrote what, when and why?

Indo-European influence is usually linked to Carolina Josephina von Franquemont. But can this influence truly be traced back to one individual? What other factors have had a role in this development?

European interest in Batik

In the 19th century the interest for Batik in Europe grew. Museums started buying Batiks, Batiks were shown during Colonial Exhibitions and people, mostly white Dutch men, started researching Batik.

The first to write about Carolina Josephina von Franquemont was Gerret Pieter Rouffaer (1860-1928). In his book ‘De Batik-kunst van Nederlandsch-Indië en haar geschiedenis’ published in 1914 Rouffaer writes in more detail about Von Franquemont. This book is still seen today as an important source for information on Batik. His writing on, and the Batiks he attributed to Von Franquemont, start a century long fascination for Von Franquemont.

Other researchers and conservators such as Tropenmuseum conservators Johanna Pape-van Steenacker (1901-1978), Rita Bolland (1919-2006), Itie van Hout and Daan van Dartel have added to this information over time. In the book ‘Splendid symbols, Textiles and traditions from Indonesia’ by Dr. Mattiebelle Gittinger, published in 1979 Von Franquemonts alleged death is described for the first time. “The secrets of this dye (…) perished with the woman herself in an earthquake in June 1867”.

Over time the earthquake turned into a volcanic eruption, and this version of the story about her death has been repeated till today.

When I started my research the first thing I started looking for was information on her death and the possible location of her Batikworkshop. On a blog about Indo-European family trees, a newspaper message was shared. The author of the blog, Roel de Neve, did not realise what Batik history he had uncovered; “Today, after a long sickbed, Miss C. J. Von Franquemont, our beloved sister, passed away”. The obituary, sent in by her brother, confirmed Von Franquemont was not swept away by an earthquake, nor by a Volcanic eruption, but that she had passed away after a long sickbed. For Modemuze I wrote a post about this with the title ‘Verzwolgen en verdwenen: de batik erfenis van Franquemont’. This blogpost marked the start of my ongoing research.

Batik Belanda

In 1993 the book ‘Batik Belanda’ by Harmen Veldhuisen (1943-2020) was published. In his book he describes a specific style within Batik which was according, to Veldhuisen, made by and for European and Indo-European women in the former Dutch East Indies. Von Franquemont is put in the book as the starter of this trend as the so-called ‘Mother of Batik Belanda’.

I got fascinated by this history. In Europe we almost always mention these ‘Indo-European Batiks’ first, while this history is often just a footnote in Indonesia and most Batikmakers never even heard of it. The book ‘Batik Belanda’ was published also in Bahasa Indonesia. For most Indonesians the book is the first time they learn about these European influenced Batiks. A large part of the Veldhuisen Batik collection ended up in the Tropenmuseum, the other part went to Danar Hadi, the private Batikmuseum in Solo on Java. A special room in the museum is dedicated to ‘Batik Belanda’.

Veldhuisen coined the term ‘Batik Belanda’, but actually this term for Batiks was not use in the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

The growing interest in Europe for Batik in the 19th century, was not just because they thought it was beautiful, they thought Batik was an interesting business opportunity. When Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781-1826) described the Batik technique in his book ‘The History of Java’, published in 1817, Raffles did this because he thought it would be a good idea to make imitations. These imitations would be made in England and then shipped to Asia to be sold there. Other cotton-printing compagnies in Europe started making these fake Batiks as well and shipped them to SouthEast Asia.

From the 1850’s onwards imitation Batiks were made in the Netherlands, Switzerland, France and England. These imitations from Europe or fake Batik, became known as Batik Belanda.

The imitation Batiks were made partly by machines and partly by hand. The machines had copper rolls that would print a motif on the cloth using a kind of resin. The blue was dyed in a colour bath and other colours were added with block printing.

In response to these cheaper fake Batiks, the Batik Cap industry on Java grew throughout the mid-19th century. Batik Cap was faster to produce than Batik Tulis. It was therefor also cheaper.

Batik Cap was great for competing with the imitations from Europe. The imitations were cheap, but people on Java preferred real Batik. They would buy Batik Cap, or save money to buy Batik Tulis. The European cotton-printers were baffled that their cheap mass produced imitations would not sell. It was actually the earliest form of fast fashion and it was not very successful.

Samuel Cornelis Jan Willem van Musschenbroek (1827-1883) writes in 1878 about imitations the following: “But, keep in mind, always as imitation (Batik tiron), or Batik welondå, Dutch Batik, a Batik ‘of its own kind’. Never did Javanese people see the imitation for (real) Javanese Batik”

For the platform Things That Talk run by research associate Fresco Sam-Sin, I made a page, a zone, within the website to share more on one of the Dutch cotton-printing compagnies, De Leidsche Katoenmaatschappij LKM). In the zone ‘Fabric(s) of Leiden’ students unravel the stories behind objects from collections like the Museum Volkenkunde and Wereldmuseum to uncover the history and legacy of the LKM.

Provenance

Next to literature (1) research, I started working out the provenance of all Batiks attributed, at one point in time, to Von Franquemont within the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (NMvW) and the Wereldmuseum.

In this process I found pieces that were attributed to her, but were never used in publications, also some had not been photographed yet or only had partial pictures. So new photos were taken for the NMvW Museum System (TMS) database of all Batiks I looked at.

An essay on the Provenance of the Prankemon sarongs while be published later this year, hopefully in June, in the publication Provenance #4 by NMvW/Wereldmuseum

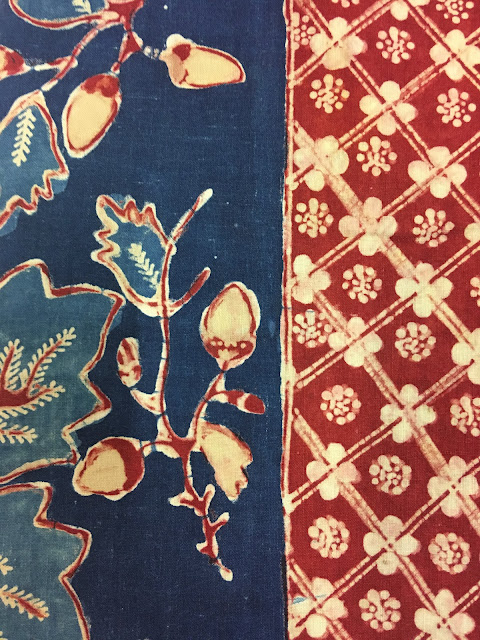

With all the research I did on Batiks attributed to Von Franquemont, I noticed how important it is to know the wearer. Batiks in museum collections have often limited provenance, especially if it is bought from a collector. Not always is written down if the person who donated the Batiks actually wore the Batiks themselves, but the family tree can sometimes provide some insights on to whom the Batiks belonged. If a family member did live in the former Dutch East Indies, it could be that the Batiks might have been worn by them. So with little information you can sometimes still find out a lot. Extensive collections have been kept in the Netherlands, privately and in museum-collections. These kept Batik-collections can give us new interesting insights and different angles on how to share this history.

Already from looking at a Batik you can often tell if it was worn or not. Many of the pieces in the Dutch collections were specifically collected for the museum and thus were never worn.

So I always get extra excited if a piece has been worn, because worn pieces can tell us more than the unworn ones. Markers for Batiks being worn are that the sarongs are sown together or were sown together, have a faded colour and sometimes even mended parts.

During The Association of Dress Historians Annual New Research Conference 2022 I shared my current research that is focussed more on the wearer, especially on ladies that were of European descent, who dressed in Batik sarongs themselves, during colonial times in Indonesia. For this presentation I focussed on 41 Batiks from the Tropenmuseum collection, TM-2899-1 - TM-2899-41, that were donated by Jonkvrouwe Anna Cecile Aurélie Jeanne Clifford (1884-1960), Jonkvrouwe as in damsel. Hence the title ‘A Batik collection fit for a Lady’. Daan van Dartel, my research advisor & Curator of Fashion at the Tropenmuseum already published on Lily, as she was called for short, in the booklet ‘Collectors Collected’.

Lily’s donation is an unusual wardrobe for a lady whom apparently had never been to Indonesia herself. The Batiks most likely belonged to her mother, Theodora Adriana Lammers van Toorenburg, who was born in 1852 in the former Dutch East Indies. This collection provides us with interesting insights into what was worn by whom and how the wearer can provide us with provenance that is often overlooked in Batik-research.

I will turn this presentation into an article for The journal of Dress History. In Dutch a shorter article by me about this was already published in the magazine Batik!

Prankemon Green

Next to the provenance, I am working on an analysis of the dyes used in the Von Franquemont Batiks. According to Rouffaer she was famous for her natural and colourfast green. However the Batiks have never been examined to determine what specific dye was actually used.

Together with Art Proaño Gaibor of Rijksdienst van Cultureel Erfgoed (RCE) we made a plan to examine the dyes. Nowadays with a very small sample research can be done on the type of dye, natural or synthetic, what materials were used to recreate the dye or if mordants were used.

I selected 5 Batiks that had the best provenance. Not that we know for certain these were made by Von Franquemont, this cannot be said of any Batiks I looked at. But these 5 Batiks had a clear date of entering the collection and from which person the donation came. From 5 Batiks we took samples of each colour. A sample is just 2 mm of one thread. As a little premiere I can share that all dyes in the 5 Batiks are made from natural materials. Although all 5 Batiks were attributed to Von Franquemont at one point in time, all 5 are dyed differently, which tells us that they seem to be from 5 different workshops. We are working out the differences between the dyes in a report that will be publicly available soon.

Future of Batik

When it comes down to re-telling the history of the (Indo-)European influence on Batik there is still much to explore.

For the current display showing Batiks with an ‘Indo-European influence’ at the Wereldmuseum Rotterdam that opened in 2020, I advised for the selection of Batiks. I also wrote a three part article on these Batiks for the magazine ‘Tribale Kunst’. It was later published in a shorter English version in the Textile Asia Journal.

If I look at this display now, I think we might show Batiks from the past differently in the future. All these Batiks have an interesting story to tell, but by grouping them in this way, we loose part of the story, specifically the Asian side of the story. The focus is now often on facts that cannot be checked nor proven, while the new uncovered data isn’t used, yet. I hope that my re-telling of this history provides us with more interesting, but above all more correct, layered stories.

Detail of Batik bedcover donated by a niece of Von Franquemont

WM-26938, collection Wereldmuseum Rotterdam

1) Literature examples in which Carolina Josephina von Franquemont is mentioned, aside from the books mentioned in this blogpost:

‘Batikken’ in the Encyclopedie van Nederlandsch-Indië (1917) Gerret Pieter Rouffaer

‘Das Batiken, eine Blüte indonesischen Kunstlebens’ (1926) J.A. Loebèr

‘Batiks from Java, The refined beauty of an ancient Craft’ (1960) Rita Bolland, Dr. J. H. Jager Gerlings and L. Langewis, Tropenmuseum

Catalog ‘Fabric of Enchantment, batik from the North coast of Java’ (1997) Inger McCabe Elliot, Rens Heringa and Harmen Veldhuisen, LACMA

‘Building on Batik: The Globalization of a Craft Community’ (2000) Michael Hitchcock

‘Batik, Drawn in wax, 200 years of batik art from Indonesia in the Tropenmuseum collection’ (2001), Itie van Hout, KIT Publishers

‘Batik: Design, Style & History’ (2004) Fiona Kerlogue

‘Batik Design’ (2004) Pepin van Roojen

‘Glory of Batik, The Danar Hadi Collection’ (2011) J. Achjadi

Catalog ‘Batik Pesisir, An Indonesian Heritage, Collection of Hartono Sumarsono’ (2012) Helen Ishwara

‘Batik: From the Courts of Java and Sumatra’ (2014) Rudolf Smend

Catalog ‘Asian art and Dutch taste’ (2014) Jan Veenendaal, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Catalog ‘Sarong Kebaya, Peranakan Fashion in an interconnected World, 1500-1950’ (2015), Peter Lee, ACM

Catalog 'A Royal Treasure, the Javanese Batik collection of King Chulalongkorn of Siam' (2019) Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles in Bangkok, Thailand

Catalog ‘Batik, Traces through time, Batik collections in the National Museum’ (2021) Fiona Kerlogue, National Museum, Prague, Czech republic

2) Indo, from Indo-European, is written between brackets in my research title because the influence is not always Indo-European, but more often directly European. To include both, Indo-European and European in my title, I choose to write it as ‘(Indo-)European’

Author

Sabine Bolk, artist & Batik researcher. Blogger for the blog ’The journey to Batik’ and Modemuze. Research Associate at the Research Center for Material Culture in Leiden from 2019-2021. Currently working on new research with the focus on the wearer.